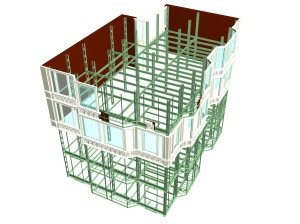

The image is another one by ace 3dmax artist Ryan Risse, and it’s the cover image for the current Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians issue, which includes the article on wind bracing that I presented at Northwestern last month. (Fans of riveting, or those interested in how metallurgy can influence building form and planning can download the paper on my home page–the download is free but U of C Press copyright restrictions apply).

The image is another one by ace 3dmax artist Ryan Risse, and it’s the cover image for the current Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians issue, which includes the article on wind bracing that I presented at Northwestern last month. (Fans of riveting, or those interested in how metallurgy can influence building form and planning can download the paper on my home page–the download is free but U of C Press copyright restrictions apply).

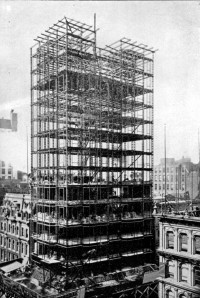

The Reliance is one of the city’s best known skyscrapers, but it was almost accidental in its conception and design. William Hale, a former elevator entrepreneur, commissioned Burnham & Root to design a fourteen-story building in 1890, but leases in the existing four-story building ran through 1894. Hale, undeterred, paid for the top three stories to be held in the air by jackscrews while new foundations and a new ground floor shop (first occupied by Carson, Pirie, Scott). The existing tenants were thus “undisturbed,” though the sensation of doing business above an open excavation must have shaded things a bit.

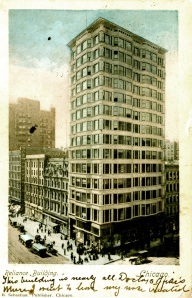

In 1894, of course, the city was in the midst of a depression, and the original scheme was abandoned. Hale instead asked Burnham and Root’s replacement, Charles Bowler Atwood, to design a tower to compete with the Columbus Memorial Building, completed in 1893, directly across the street. Rather than rely on commercial tenants, the Columbus offered examination and consultation space to doctors on its upper floors, and Hale conceived the Reliance, in large part, as a downtown clinic, to be rented hourly, by suburban doctors who could more easily see their patients closer to their place of work.

The radical composition of the Reliance’s skin suggests a neat parallel between the collapse of glass prices in the mid-1890s and the need for such medical space to provide huge quantities of daylight. Atwood specified 6′-0″ square lights of plate glass flanked by operable, double hung windows in cantilevered oriels, making the exterior of the building something over 85% glass. “The windows,” Scientific American noted, “were made as large as the situation of the columns would allow. In the skin’s interstices, he specified white enameled terra cotta, which Burnham and Root had used, experimentally, on the Rand-McNally Building of 1890. Here, it offered the promise of washability, in line with the hygienic aims of the building’s medical program.

The Reliance’s extraordinarily narrow proportions led Burnham’s engineer, E. C. Shankland, to design a frame with moment-resisting connections between girders and beams throughout the building’s perimeter. These connections represented one of the first installations of a laterally-resistant steel frame that did not require cross- or knee-bracing, and it relied on Gray columns, riveted connections, and deep girders to ensure that any wind forces were carried from girder to column on what Shankland termed the “table leg principle.” The stiff connections ensured that any axial forces carried through the girders would be resisted by the columns’ ability to absorb bending. This eliminated the planning problems of shear walls or truss panels internally.

The Reliance's steel frame. Note the lack of cross bracing and (if you look closely) the open spaces within the Gray columns

While generations of later modernists would claim the Reliance’s glassy skin and thinly veiled steel skeleton as forebears, the building met with stiff criticism in its day. Writing for Inland Architect in 1896, New York critic Barr Ferree claimed that its strict adherence to the tenacious proportions of its steel frame–exactly what makes it seem so prescient today–was not only ugly, but actually disturbing:

“Not only are there structural reasons prohibiting the direct employment of the metal frame as a basis in the design of high buildings, but those structures in which the architectural framework has been reduced to the smallest limit, so that the building is little more than a skeleton of brick or terra cotta, show how unsatisfactory such a treatment is aesthetically. The Reliance building, in Chicago, is, perhaps, the most notable attempt yet made to reduce the amount of the inclosing material to a minimum, and the design is scarcely more than a huge house of glass divided by horizontal and vertical lines of white-enameled brick. The Fisher building, in the same city, and the Mabley building, in Detroit, are other examples illustrating the same tendency, though in not quite so pronounced a fashion as in the first instance. It is a good principle in architecture that a building should not only be firm and strong, but that it should seem so. This reasonable requirement is not fulfilled in these designs.”

Along with the Fisher, the Reliance shows the rapid acceptance of the divorce between self-braced frame and thin, curtain-like skin that would come to dominate skyscraper construction in the twentieth century. While it was not quite as great a structural achievement as the Fisher (its party-line walls offered considerable lateral resistance, too, whether Shankland designed them this way or not), it enjoyed a significantly greater afterlife as historians and architects sought early hints of modernism. After a stellar restoration by Antunovich Associates and T. Gunny Harboe of McClier Corp , the Reliance is now the Hotel Burnham, whose restaurant is named after Atwood.

Great article on WLJ and riveted construction. Thanks for posting.

LikeLike