Taxonomy

| Information science |

|---|

| General aspects |

| Related fields and subfields |

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

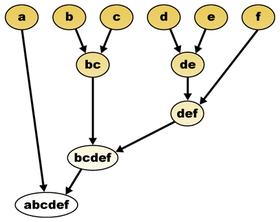

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. Among other things, a taxonomy can be used to organize and index knowledge (stored as documents, articles, videos, etc.), such as in the form of a library classification system, or a search engine taxonomy, so that users can more easily find the information they are searching for. Many taxonomies are hierarchies (and thus, have an intrinsic tree structure), but not all are.

Originally, taxonomy referred only to the categorisation of organisms or a particular categorisation of organisms. In a wider, more general sense, it may refer to a categorisation of things or concepts, as well as to the principles underlying such a categorisation. Taxonomy organizes taxonomic units known as "taxa" (singular "taxon")."

Taxonomy is different from meronomy, which deals with the categorisation of parts of a whole.

Etymology[edit]

The word was coined in 1813 by the Swiss botanist A. P. de Candolle and is irregularly compounded from the Greek τάξις, taxis 'order' and νόμος, nomos 'law', connected by the French form -o-; the regular form would be taxinomy, as used in the Greek reborrowing ταξινομία.[1][2]

Applications[edit]

Wikipedia categories form a taxonomy,[3] which can be extracted by automatic means.[4] As of 2009[update], it has been shown that a manually-constructed taxonomy, such as that of computational lexicons like WordNet, can be used to improve and restructure the Wikipedia category taxonomy.[5]

In a broader sense, taxonomy also applies to relationship schemes other than parent-child hierarchies, such as network structures. Taxonomies may then include a single child with multi-parents, for example, "Car" might appear with both parents "Vehicle" and "Steel Mechanisms"; to some however, this merely means that 'car' is a part of several different taxonomies.[6] A taxonomy might also simply be organization of kinds of things into groups, or an alphabetical list; here, however, the term vocabulary is more appropriate. In current usage within knowledge management, taxonomies are considered narrower than ontologies since ontologies apply a larger variety of relation types.[7]

Mathematically, a hierarchical taxonomy is a tree structure of classifications for a given set of objects. It is also named containment hierarchy. At the top of this structure is a single classification, the root node, that applies to all objects. Nodes below this root are more specific classifications that apply to subsets of the total set of classified objects. The progress of reasoning proceeds from the general to the more specific.

By contrast, in the context of legal terminology, an open-ended contextual taxonomy is employed—a taxonomy holding only with respect to a specific context. In scenarios taken from the legal domain, a formal account of the open-texture of legal terms is modeled, which suggests varying notions of the "core" and "penumbra" of the meanings of a concept. The progress of reasoning proceeds from the specific to the more general.[8]

History[edit]

Anthropologists have observed that taxonomies are generally embedded in local cultural and social systems, and serve various social functions. Perhaps the most well-known and influential study of folk taxonomies is Émile Durkheim's The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. A more recent treatment of folk taxonomies (including the results of several decades of empirical research) and the discussion of their relation to the scientific taxonomy can be found in Scott Atran's Cognitive Foundations of Natural History. Folk taxonomies of organisms have been found in large part to agree with scientific classification, at least for the larger and more obvious species, which means that it is not the case that folk taxonomies are based purely on utilitarian characteristics.[9]

In the seventeenth century the German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz, following the work of the thirteenth-century Majorcan philosopher Ramon Llull on his Ars generalis ultima, a system for procedurally generating concepts by combining a fixed set of ideas, sought to develop an alphabet of human thought. Leibniz intended his characteristica universalis to be an "algebra" capable of expressing all conceptual thought. The concept of creating such a "universal language" was frequently examined in the 17th century, also notably by the English philosopher John Wilkins in his work An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language (1668), from which the classification scheme in Roget's Thesaurus ultimately derives.

Taxonomy in various disciplines[edit]

Natural sciences[edit]

Taxonomy in biology encompasses the description, identification, nomenclature, and classification of organisms. Uses of taxonomy include:

- Alpha taxonomy, the description and basic classification of new species, subspecies, and other taxa

- Linnaean taxonomy, the original classification scheme of Carl Linnaeus

- rank-based scientific classification as opposed to clade-based classification

- Evolutionary taxonomy, traditional post-Darwinian hierarchical biological classification

- Numerical taxonomy, various taxonomic methods employing numeric algorithms

- Phenetics, system for ordering species based on overall similarity

- Phylogenetics, biological taxonomy based on putative ancestral descent of organisms

- Plant taxonomy

- Virus classification, taxonomic system for viruses

- Folk taxonomy, description and organization, by individuals or groups, of their own environments

- Nosology, classification of diseases

- Soil classification, systematic categorization of soils

Business and economics[edit]

Uses of taxonomy in business and economics include:

- Corporate taxonomy, the hierarchical classification of entities of interest to an enterprise, organization or administration

- Economic taxonomy, a system of classification for economic activity

- Global Industry Classification Standard, an industry taxonomy developed by MSCI and Standard & Poor's (S&P)

- Industry Classification Benchmark, an industry classification taxonomy launched by Dow Jones and FTSE

- International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC), a United Nations system for classifying economic data

- North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), used in Canada, Mexico, and the United States of America

- Pavitt's Taxonomy, classification of firms by their principal sources of innovation

- Standard Industrial Classification, a system for classifying industries by a four-digit code

- United Kingdom Standard Industrial Classification of Economic Activities, a Standard Industrial Classification by type of economic activity

- EU taxonomy for sustainable activities, a classification system established to clarify which investments are environmentally sustainable, in the context of the European Green Deal.

- Records management taxonomy, the representation of data, upon which the classification of unstructured content is based, within an organization.

- XBRL Taxonomy, eXtensible Business Reporting Language

- SRK taxonomy, in workplace user-interface design

Computing[edit]

Software engineering[edit]

Vegas et al.[10] make a compelling case to advance the knowledge in the field of software engineering through the use of taxonomies. Similarly, Ore et al.[11] provide a systematic methodology to approach taxonomy building in software engineering related topics.

Several taxonomies have been proposed in software testing research to classify techniques, tools, concepts and artifacts. The following are some example taxonomies:

Engström et al.[14] suggest and evaluate the use of a taxonomy to bridge the communication between researchers and practitioners engaged in the area of software testing. They have also developed a web-based tool[15] to facilitate and encourage the use of the taxonomy. The tool and its source code are available for public use.[16]

Other uses of taxonomy in computing[edit]

- Flynn's taxonomy, a classification for instruction-level parallelism methods

- Folksonomy, classification based on user's tags

- Taxonomy for search engines, considered as a tool to improve relevance of search within a vertical domain

- ACM Computing Classification System, a subject classification system for computing devised by the Association for Computing Machinery

Education and academia[edit]

Uses of taxonomy in education include:

- Bloom's taxonomy, a standardized categorization of learning objectives in an educational context

- Classification of Instructional Programs, a taxonomy of academic disciplines at institutions of higher education in the United States

- Mathematics Subject Classification, an alphanumerical classification scheme based on the coverage of Mathematical Reviews and Zentralblatt MATH

- SOLO taxonomy, Structure of Observed Learning Outcome, proposed by Biggs and Collis Tax

Safety[edit]

Uses of taxonomy in safety include:

- Safety taxonomy, a standardized set of terminologies used within the fields of safety and health care

- Human Factors Analysis and Classification System, a system to identify the human causes of an accident

- Swiss cheese model, a model used in risk analysis and risk management propounded by Dante Orlandella and James T. Reason

- A taxonomy of rail incidents in Confidential Incident Reporting & Analysis System (CIRAS)

Other taxonomies[edit]

- Military taxonomy, a set of terms that describe various types of military operations and equipment

- Moys Classification Scheme, a subject classification for law devised by Elizabeth Moys

Research publishing[edit]

Citing inadequacies with current practices in listing authors of papers in medical research journals, Drummond Rennie and co-authors called in a 1997 article in JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association for

a radical conceptual and systematic change, to reflect the realities of multiple authorship and to buttress accountability. We propose dropping the outmoded notion of author in favor of the more useful and realistic one of contributor.[17]: 152

Since 2012, several major academic and scientific publishing bodies have mounted Project CRediT to develop a controlled vocabulary of contributor roles.[18] Known as CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy), this is an example of a flat, non-hierarchical taxonomy; however, it does include an optional, broad classification of the degree of contribution: lead, equal or supporting. Amy Brand and co-authors summarise their intended outcome as:

Identifying specific contributions to published research will lead to appropriate credit, fewer author disputes, and fewer disincentives to collaboration and the sharing of data and code.[17]: 151

As of mid-2018, this taxonomy apparently restricts its scope to research outputs, specifically journal articles; however, it does rather unusually "hope to … support identification of peer reviewers".[18] (As such, it has not yet defined terms for such roles as editor or author of a chapter in a book of research results.) Version 1, established by the first Working Group in the (northern) autumn of 2014, identifies 14 specific contributor roles using the following defined terms:

- Conceptualization

- Methodology

- Software

- Validation

- Formal Analysis

- Investigation

- Resources

- Data curation

- Writing – Original Draft

- Writing – Review & Editing

- Visualization

- Supervision

- Project Administration

- Funding acquisition

Reception has been mixed, with several major publishers and journals planning to have implemented CRediT by the end of 2018, whilst almost as many are not persuaded of the need or value of using it. For example,

The National Academy of Sciences has created a TACS (Transparency in Author Contributions in Science) webpage to list the journals that commit to setting authorship standards, defining responsibilities for corresponding authors, requiring ORCID iDs, and adopting the CRediT taxonomy.[19]

The same webpage has a table listing 21 journals (or families of journals), of which:

- 5 have, or by end 2018 will have, implemented CRediT,

- 6 require an author contribution statement and suggest using CRediT,

- 8 do not use CRediT, of which 3 give reasons for not doing so, and

- 2 are uninformative.

The taxonomy is an open standard conforming to the OpenStand principles,[20] and is published under a Creative Commons licence.[18]

Taxonomy for the web[edit]

Websites with a well designed taxonomy or hierarchy are easily understood by users, due to the possibility of users developing a mental model of the site structure.[21]

Guidelines for writing taxonomy for the web include:

- Mutually exclusive categories can be beneficial. If categories appear in several places, it is called cross-listing or polyhierarchical. The hierarchy will lose its value if cross-listing appears too often. Cross-listing often appears when working with ambiguous categories that fits more than one place.[21]

- Having a balance between breadth and depth in the taxonomy is beneficial. Too many options (breadth), will overload the users by giving them too many choices. At the same time having a too narrow structure, with more than two or three levels to click-through, will make users frustrated and might give up.[21]

Is-a and has-a relationships, and hyponymy[edit]

Two of the predominant types of relationships in knowledge-representation systems are predication and the universally quantified conditional. Predication relationships express the notion that an individual entity is an example of a certain type (for example, John is a bachelor), while universally quantified conditionals express the notion that a type is a subtype of another type (for example, "A dog is a mammal", which means the same as "All dogs are mammals").[22]

The "has-a" relationship is quite different: an elephant has a trunk; a trunk is a part, not a subtype of elephant. The study of part-whole relationships is mereology.

Taxonomies are often represented as is-a hierarchies where each level is more specific than the level above it (in mathematical language is "a subset of" the level above). For example, a basic biology taxonomy would have concepts such as mammal, which is a subset of animal, and dogs and cats, which are subsets of mammal. This kind of taxonomy is called an is-a model because the specific objects are considered as instances of a concept. For example, Fido is-an instance of the concept dog and Fluffy is-a cat.[23]

In linguistics, is-a relations are called hyponymy. When one word describes a category, but another describe some subset of that category, the larger term is called a hypernym with respect to the smaller, and the smaller is called a "hyponym" with respect to the larger. Such a hyponym, in turn, may have further subcategories for which it is a hypernym. In the simple biology example, dog is a hypernym with respect to its subcategory collie, which in turn is a hypernym with respect to Fido which is one of its hyponyms. Typically, however, hypernym is used to refer to subcategories rather than single individuals.

Research[edit]

Researchers reported that large populations consistently develop highly similar category systems. This may be relevant to lexical aspects of large communication networks and cultures such as folksonomies and language or human communication, and sense-making in general.[24][25]

See also[edit]

- All pages with titles containing Taxonomy

The dictionary definition of taxonomy at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of taxonomy at Wiktionary The dictionary definition of classification scheme at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of classification scheme at Wiktionary- Categorization, the process of dividing things into groups

- Classification (general theory)

- Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Recognition, a fictional Chinese encyclopedia with an "impossible" taxonomic scheme

- Conflation

- Faceted classification

- Folksonomy

- Gellish English dictionary, a taxonomy in which the concepts are arranged as a subtype–supertype hierarchy

- Hypernym

- Knowledge representation

- Lexicon

- Ontology (information science), formal representation of knowledge as a set of concepts within a domain

- Philosophical language

- Protégé (software)

- Semantic network

- Semantic similarity network

- Structuralism

- Systematics

- Taxon, a population of organisms that a taxonomist adjudges to be a unit

- Taxonomy for search engines

- Thesaurus (information retrieval)

- Typology (disambiguation)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1910. (partially updated December 2021), s.v.

- ^ review of Aperçus de Taxinomie Générale in Nature 60:489–490 Archived 2023-01-26 at the Wayback Machine (1899)

- ^ Zirn, Cäcilia, Vivi Nastase and Michael Strube. 2008. "Distinguishing Between Instances and Classes in the Wikipedia Taxonomy" (video lecture). Archived 2019-12-20 at the Wayback Machine 5th Annual European Semantic Web Conference (ESWC 2008).

- ^ S. Ponzetto and M. Strube. 2007. "Deriving a large scale taxonomy from Wikipedia" Archived 2017-08-14 at the Wayback Machine. Proc. of the 22nd Conference on the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, pp. 1440–1445.

- ^ S. Ponzetto, R. Navigli. 2009. "Large-Scale Taxonomy Mapping for Restructuring and Integrating Wikipedia". Proc. of the 21st International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI 2009), Pasadena, California, pp. 2083–2088.

- ^ Jackson, Joab. "Taxonomy's not just design, it's an art," Archived 2020-02-05 at the Wayback Machine Government Computer News (Washington, D.C.). September 2, 2004.

- ^ Suryanto, Hendra and Paul Compton. "Learning classification taxonomies from a classification knowledge based system." Archived 2017-08-09 at the Wayback Machine University of Karlsruhe; "Defining 'Taxonomy'," Archived 2017-08-09 at the Wayback Machine Straights Knowledge website.

- ^ Grossi, Davide, Frank Dignum and John-Jules Charles Meyer. (2005). "Contextual Taxonomies" in Computational Logic in Multi-Agent Systems, pp. 33–51[dead link].

- ^ Kenneth Boulding; Elias Khalil (2002). Evolution, Order and Complexity. Routledge. ISBN 9780203013151. p. 9

- ^ Vegas, S. (2009). "Maturing software engineering knowledge through classifications: A case study on unit testing techniques". IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. 35 (4): 551–565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.221.7589. doi:10.1109/TSE.2009.13. S2CID 574495.

- ^ Ore, S. (2014). "Critical success factors taxonomy for software process deployment". Software Quality Journal. 22 (1): 21–48. doi:10.1007/s11219-012-9190-y. S2CID 18047921.

- ^ Utting, Mark (2012). "A taxonomy of model-based testing approaches". Software Testing, Verification & Reliability. 22 (5): 297–312. doi:10.1002/stvr.456. S2CID 6782211. Archived from the original on 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

- ^ Novak, Jernej (May 2010). "Taxonomy of static code analysis tools". Proceedings of the 33rd International Convention MIPRO: 418–422. Archived from the original on 2022-06-27. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ Engström, Emelie (2016). "SERP-test: a taxonomy for supporting industry–academia communication". Software Quality Journal. 25 (4): 1269–1305. doi:10.1007/s11219-016-9322-x. S2CID 34795073.

- ^ "SERP-connect". Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-08-28.

- ^ Engstrom, Emelie (4 December 2019). "SERP-connect backend". GitHub. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ a b Brand, Amy; Allen, Liz; Altman, Micah; Hlava, Marjorie; Scott, Jo (1 April 2015). "Beyond authorship: attribution, contribution, collaboration, and credit". Learned Publishing. 28 (2): 151–155. doi:10.1087/20150211. S2CID 45167271.

- ^ a b c "CRediT". CASRAI. CASRAI. 2 May 2018. Archived from the original (online) on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "Transparency in Author Contributions in Science (TACS)" (online). National Academy of Sciences. 2018. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "OpenStand". OpenStand. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ a b c Peter., Morville (2007). Information architecture for the World Wide Web. Rosenfeld, Louis., Rosenfeld, Louis. (3rd ed.). Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly. ISBN 9780596527341. OCLC 86110226.

- ^ Ronald J. Brachman; What IS-A is and isn't. An Analysis of Taxonomic Links in Semantic Networks Archived 2020-06-30 at the Wayback Machine. IEEE Computer, 16 (10); October 1983.

- ^ Brachman, Ronald (October 1983). "What IS-A is and isn't. An Analysis of Taxonomic Links in Semantic Networks". IEEE Computer. 16 (10): 30–36. doi:10.1109/MC.1983.1654194. S2CID 16650410.

- ^ "Why independent cultures think alike when it comes to categories: It's not in the brain". phys.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Guilbeault, Douglas; Baronchelli, Andrea; Centola, Damon (12 January 2021). "Experimental evidence for scale-induced category convergence across populations". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 327. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..327G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20037-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7804416. PMID 33436581.

Available under CC BY 4.0 Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Available under CC BY 4.0 Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

References[edit]

- Atran, S. (1993) Cognitive Foundations of Natural History: Towards an Anthropology of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43871-1

- Carbonell, J. G. and J. Siekmann, eds. (2005). Computational Logic in Multi-Agent Systems, Vol. 3487. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.ISBN 978-3-540-28060-6

- Malone, Joseph L. (1988). The Science of Linguistics in the Art of Translation: Some Tools from Linguistics for the Analysis and Practice of Translation. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-887-06653-5; OCLC 15856738

- *Marcello Sorce Keller, "The Problem of Classification in Folksong Research: a Short History", Folklore, XCV(1984), no. 1, 100–104.

- Chester D Rowe and Stephen M Davis, 'The Excellence Engine Tool Kit'; ISBN 978-0-615-24850-9

- Härlin, M.; Sundberg, P. (1998). "Taxonomy and Philosophy of Names". Biology and Philosophy. 13 (2): 233–244. doi:10.1023/a:1006583910214. S2CID 82878147.

- Lamberts, K.; Shanks, D.R. (1997). Knowledge, Concepts, and Categories. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780863774911.

External links[edit]

Media related to Taxonomy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Taxonomy at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of taxonomy at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of taxonomy at Wiktionary- Taxonomy 101: The Basics and Getting Started with Taxonomies