The Capuçon brothers are ready for the big screen

It is easy to imagine that a pair of French classical musical prodigies like the Capuçon brothers — who began to play their instruments before kindergarten — would not be particularly open to modernity. Given that Renaud, a leading violinist, and Gautier, a top cellist of his generation, are preparing to take part in a decidedly modern and Hollywood-flavored concert series in Los Angeles in early June, this would be a problem.

In a four-night run that starts June 2, les frères Capuçon will join the charismatic Venezuelan-born musical director Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic in performing Brahms’ Double Concerto and Symphony No. 4 at Walt Disney Concert Hall. The final June 5 afternoon show aims to offer an immersive sights-and-sounds experience that is slated to include rehearsal footage and live interviews with performers before and after the show — and it will be simulcast live in about 450 movie theaters around North America. This reality TV-meets-classical music spectacle will be hosted by actor John Lithgow.

So how do a pair of virtuosos known for their musical sensitivity, expressiveness and creative desire to work with people who they like and trust perceive the idea of invasive cameras projecting their preshow preparations and high art live to tens of thousands of moviegoers who pass by the concession stand?

Interviewed in the cafe of an old-school Parisian hotel recently, Renaud’s response was notably down to earth: “Beyond the magnificent music, the idea of people eating popcorn and drinking Cokes and watching us — a couple of French guys who show up in Los Angeles to play Brahms — is very exciting.”

His younger brother lauded efforts to modernize live classical performances that have changed little in recent decades. “People are sitting there and playing. It can be beautiful, but it isn’t spectacular like an opera or a film. There are no special effects. But now you can film it and give the event a [storytelling] rhythm,” Gautier explained. “This is a completely modern way of looking at classical music. There won’t be different lighting or a glittering [disco] ball, but the audience will see backstage before the concert, and after, the adrenaline rising.”

Despite their youth — Renaud is 35, Gautier is 30 — they already have a great deal of experience in their very traditional milieu.

Renaud took up the violin when he was 4. He explained that he immediately took pleasure from collaborating with other students who lived near his family in Chambéry in the French Alps, and that he felt strangely focused on the instrument while still in preschool. “Maybe I would have been as interested if those courses were pottery,” he said with a laugh.

He began with Vivaldi. “By the time I was 8, I knew I wanted to keep the violin with me,” Renaud said, before recounting the story of a record seller who was stunned to hear a child’s voice asking for the latest Stravinsky recording and seeing the top of the head of an 8-year-old boy across the counter.

Gautier’s relationship to music was more individual, and it began later in life — when he was nearly 5. “I adored it from the start,” Gautier said of his first encounter with the cello. “I loved the sonorities, the timbre.” A broad-minded music teacher cultivated the boy’s intuitive love of the instrument and told him that classical and chamber music “has to swing.” That advice, Gautier said, serves him even now. “I didn’t wake up one day and say, ‘I want to be a soloist,’ but I knew when I was 10 or 12 that I would spend my life with this instrument.”

The brothers did not grow up playing music together because of their age gap and because Renaud left home when he was 14 to study at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris, but they began to collaborate after Gautier turned 15. They have performed numerous concerts together, including a U.S. recital tour, and have released half a dozen recordings, including a DVD of cello and violin interpretations of 20th century compositions, “Face à Face.”

Brahms is particularly special to the brothers because his music has accompanied them almost from the start. Recently, they recounted, the brothers came across an old Brahms Piano Trios album that Renaud gave Gautier when he was just 8 or 9. Isaac Stern played his Guarneri del Gesù violin that was made in 1737. In a poetic twist, the brothers later recorded that same Brahms Piano Trios — with Renaud performing with that very instrument. (The Banca Svizzera Italiana purchased it for him.) “What I love about this violin is how it resonates with Brahms’ harmonies,” Renaud said. “When you have it in your hands, it is history that you are playing.”

The Capuçons, who live in France and who are each bringing up a young child, relish collaborative musicianship and a trust-filled ambiance akin to what many top-level stage and film actors seek. “During a concert, you need to know that you can take every risk. You must feel so secure that you don’t think about failure. If you think, ‘Will the other musician go along with this?,’ it is over,” says Renaud. “But when it is fluid, you have a sense of boundless liberty. For us, we need a human bond or with people with whom there is no tension.”

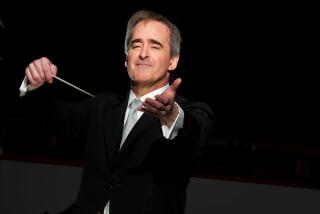

They said they find just such an atmosphere with Dudamel, who Renaud said is “emblematic of a new generation in the classical music world. There is something ‘Bernstein-esque’ about him.” Renaud first played with Dudamel when he was a teenager in the conductor’s native Venezuela as well as in Paris and Salzburg. Of the conductor’s remarkable energy, Renaud says that performing with Dudamel is like receiving “a vitamin C injection. Gustavo gives himself completely to the audience.”

“Dudamel lights up a room when he works,” interjected Gautier, who collaborated on a Salzburg Festival performance (of Beethoven’s Triple Concerto) with his brother, pianist Martha Argerich and Dudamel. “What is most fascinating — aside from him being an extraordinary musician and having a stunning physicality and technique — is the glimmer in his eyes. When I first saw him work, there was a light there, a joy to be on stage. It illuminates a room, and the public feels it.

“Sharing music with other musicians is very personal. We give our all, we share,” says Gautier, known for his musical passion as well as the lush emotion he draws from his cello. “It is a moment of great intimacy. It is something very deep. You can’t just share that sort of intimacy with just any musician.”

But, they said, they will be happy to share it with filmgoers around North America.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.