The Oranges & Lemons Churches

Click here to book for my next tour of the City of London on Sunday 21st April

St Clement’s, Eastcheap

“Oranges and lemons,” say the bells of St. Clement’s.

Site of St Martin Orgar, Martin Lane

“You owe me five farthings,” say the bells of St. Martin’s.

St Sepulchre-without-Newgate

“When will you pay me?” say the bells of Old Bailey.

St Leonard’s, Shoreditch

“When I grow rich,” say the bells of Shoreditch.

St Dunstan’s, Stepney

“When will that be?” say the bells of Stepney.

St Mary Le Bow, Cheapside

“I do not know,” says the great bell of Bow.

You may also like to take a look at

The Inescapable Melancholy Of Phone Boxes

Click here to book for my next tour of the City of London on Sunday 21st April

Red phone boxes are a cherished feature of my personal landscape because, in my childhood, we never had a telephone at home and, when I first made a phone call at the age of fifteen, it was from a box. In fact, for the major part of my life, all my calls were made from boxes – thus telephone calls and phone boxes were synonymous for me. I grew up with the understanding that you went out to make a phone call just as you went out to post a letter.

Yet the culture of mobile phones is now so pervasive I was shocked to discover I had hardly noticed as the red telephone boxes have vanished from our streets and those few that remain stand redundant and unused. So I set out with my camera to photograph the last of them, lest they should disappear without anybody noticing. It was a curious and lonely pilgrimage because, whereas they were once on every street, they have now almost all gone and I had to walk miles to find enough specimens to photograph.

Reluctantly, I must reveal that on my pitiful quest in search of phone boxes, I never saw anyone use one though I did witnessed the absurd spectacle of callers standing beside boxes to make calls on their mobiles several times. The door has fallen off the one in Spitalfields, which is perhaps for the best as it has been co-opted into service as a public toilet while the actual public toilet nearby is shut.

Although I must confess I have not used one myself for years, I still appreciate phone boxes as fond locations of emotional memory where I once experienced joy and grief at life-changing news delivered down the line. But like the horse troughs that accompany them on Clerkenwell Green and outside Christ Church, Spitalfields, phone boxes are now vestiges of a time that has passed forever. I imagine children must ask their mothers what these quaint red boxes are for.

The last phone boxes still stand proud in their red livery but like sad clowns they are weeping inside. Along with pumps, milestones, mounting blocks and porters’ rests these redundant pieces of street furniture serve now merely as arcane reminders of a lost age – except that era was the greater part of my life. This is the inescapable melancholy of phone boxes.

Ignored in Whitechapel

Abandoned in Whitechapel

Rejected in Bow

Abused in Spitalfields

Irrelevant in Bethnal Green

Shunned in Bethnal Green

Empty outside York Hall

Desolate in Hackney Rd

Pointless in St John’s Sq

Irrelevant on Clerkenwell Green

Invisible in Smithfield

Forgotten outside St Bartholomew’s Hospital

In service outside St Paul’s as a quaint location for tourist shots

You may also like to take a look at

Charles Chusseau-Flaviens’ Petticoat Lane

Click here to book for my next tour of the City of London on Sunday 21st April

Petticoat Lane

Photographer Charles Chusseau-Flaviens came to London from Paris and took these pictures, reproduced courtesy of George Eastman House, before the First World War – mostly likely in 1911. This date is suggested by his photograph of the proclamation of the coronation of George V which took place in that year. Very little is known of Chusseau-Flaviens except he founded one of the world’s first picture agencies, located at 46 Rue Bayen, and he operated through the last decade of the nineteenth and first decade of the twentieth century. Although their origin is an enigma, Chusseau-Flaviens’ photographs of London and especially of Petticoat Lane constitute a rare and precious vision of a lost world.

Petticoat Lane

Sandys Row with Frying Pan Alley to the right

Proclamation of the coronation of George V, 1911

Crossing sweeper in the West End

Policeman on the beat in Oxford Circus, Regent St

Beating the bounds for the Tower of London, Trinity Sq

Boats on the Round Pond, Kensington Gardens

Suffragette in Trafalgar Sq

Photographs courtesy George Eastman House

You may also like to take a look at

At Oitij-jo Kitchen

‘We want to celebrate the work that the women do’

People often ask where they can find authentic Bengali food in Spitalfields and I have found the answer in Oitij-jo Kitchen, a women’s collective who run the catering operation at Rich Mix Arts Centre in the Bethnal Green Rd. This Sunday April 14th you can join the Eid celebrations there and experience a traditional Bhorta Bengali New Year lunch, served from 1pm – no booking required.

Last week, Contributing Photographer Sarah Ainslie spent a morning recording the activity in the kitchen while I sat down with co-founder Maher Anjum who explained to me what it is all about, before we all reconvened for a taste test.

“Four of us set up the Oitij-jo collective in 2013 straight after the 2012 London Olympics. We had Akram Khan in the opening ceremony but nothing else. We were all creatives, so we asked ourselves ‘Where are we in this scenario?’

We set up Oitij-jo to be a platform for creative practitioners from the Bangladeshi disapora, representing them, supporting them, especially emerging artists, but also showcasing our rich cultural heritage and translating it into what is happening now. Oitij-jo in bangla means heritage. It was important to us to take it to the future, so that the next generation have an understanding and can interpret it in their own way, because it is only at that point that it is alive.

In 2016, we did a year’s residency at the Gram Bangla restaurant in Brick Lane displaying art works with a new exhibition every three months. It was the first restaurant which served traditional Bengali food, and that was when food became part of our project. We had a lot of conversations with the restauranteurs about the nature of our food. And we realised that food was such an important part our cultural identity, it was something we wanted to work with. There was a visible lack of women in the restaurant sector and in catering in general, so we decided to focus on bringing in Bangladeshi women. It’s culture that people carry, even if may not pay attention to it, we simply say ‘Have some food.’

One of the things that women who work with us tell us is, ‘People say ‘thank you’ for the food I prepare for them. That’s really nice because at home it’s taken for granted. No-one’s going to thank you for the food you put on the table, it’s come-eat-go.’ For a lot of these women, the recognition of what they are doing is a recognition of themselves and food becomes an intrinsic part of who they are, part of their identity.

British Bangladeshi women are some of the least economically active of the population this country, three times less likely to be paid the same wages as anyone else. What are we doing about it? The creative sector is one of the most productive, but the involvement of black, Asian and people from other ethnic minorities is one of the least.

We see Otijo-jo kitchen as the means of giving women the pathway to self-discovery and self-esteem, while exploring the question of what is food for the British Bangladeshi community.

The so-called colonial curry – and what is seen to be ‘curry’ – has a complicated lineage, but there is a place for it and it has made a huge contribution to the community where employment was not available. It was a way for people to establish themselves and be their own bosses, rather than waiting for a job that might never come. We need to acknowledge that but it gets complicated when we ask, ‘What is the food? Who does it? And how does it happen?’

What we want to do is something quite different. We want to celebrate the work that the women do and the food which we consider is traditional Bengali food that people eat at home.

We could not get any funding, so we did a crowdfund in 2018 and raised a tiny amount of money, and started in 2019. Since then we have worked with about sixty women. We do not expect them to stay with us because we want them to gain the ability and self-confidence, get the skills and experience, and move on to do what they want to do.

Many women who come to us have never been in paid employment, they have very little experience of being outside the home or being in a working environment. We want them to build up the confidence to say ‘I can be here’ and be able to talk to people.

We have around a dozen women working with us at present. Once the women have finished their training period, they can stay on working with us and earn the London Living Wage. While they are training with us, they get a daily bursary.

We are a charity and a social enterprise, so we have to make sure we earn money to continue this work. Over the years, we have developed menus and recipes that are our style of cooking. The women who join us learn to cook our recipes the way we cook them.

We serve food at Rich Mix each Thursday to Sunday from 3pm to 9pm. The rest of the time, we use the kitchen here to do catering. We do conferences, seminars, weddings, any kind of occasion. We provide a hundred student lunches for a university twice a week, that’s a very different kind of catering. We did a conference for the Serpentine Gallery at Somerset House for one hundred and twenty people, breakfast, tea, lunch and something in the afternoon too.

Most of the women find us through word of mouth and we are having people contacting us all the time. We have a wide range of ages from around twenty to over sixty and we feel that’s really important because they brings different skills, experiences and abilities. Women come from across Tower Hamlets and the East End.

When we first started, someone asked, ‘If people want vegan food, what shall we give?’ If you have plain rice and dhal which is a standard Bengali meal, that is vegan. Bangladesh is a nation of rivers, so our heritage is that we eat vegetarian and vegan food all the time. You could say that we are going with the trend, except that is normal traditional food for us.”

Surma Khanom, Maher Anjum, Hajira Bibi & Rohema Begum

Photographs copyright © Sarah Ainslie

You may also like to read about

Blossom Time In The East End

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

In Bethnal Green

Let me admit, this is my favourite moment in the year – when the new leaves are opening fresh and green, and the streets are full of trees in flower. Several times, in recent days, I have been halted in my tracks by the shimmering intensity of the blossom. And so, I decided to enact my own version of the eighth-century Japanese custom of hanami or flower viewing, setting out on a pilgrimage through the East End with my camera to record the wonders of this fleeting season that marks the end of winter incontrovertibly.

In his last interview, Dennis Potter famously eulogised the glory of cherry blossom as an incarnation of the overwhelming vividness of human experience. “The nowness of everything is absolutely wondrous … The fact is, if you see the present tense, boy do you see it! And boy can you celebrate it.” he said and, standing in front of these trees, I succumbed to the same rapture at the excess of nature.

In the post-war period, cherry trees became a fashionable option for town planners and it seemed that the brightness of pink increased over the years as more colourful varieties were propagated. “Look at it, it’s so beautiful, just like at an advert,” I overheard someone say yesterday, in admiration of a tree in blossom, and I could not resist the thought that it would be an advertisement for sanitary products, since the colour of the tree in question was the exact familiar tone of pink toilet paper.

Yet I do not want my blossom muted, I want it bright and heavy and shining and full. I love to be awestruck by the incomprehensible detail of a million flower petals, each one a marvel of freshly-opened perfection and glowing in a technicolour hue.

In Whitechapel

In Spitalfields

In Weavers’ Fields

In Haggerston

In Weavers’ Fields

In Bethnal Green

In Pott St

Outside Bethnal Green Library

In Spitalfields

In Bethnal Green Gardens

In Museum Gardens

In Museum Gardens

In Paradise Gardens

In Old Bethnal Green Rd

In Pollard Row

In Nelson Gardens

In Canrobert St

In the Hackney Rd

In Haggerston Park

In Shipton St

In Bethnal Green Gardens

In Haggerston

At Spitalfields City Farm

In Columbia Rd

In London Fields

Once upon a time …. Syd’s Coffee Stall, Calvert Avenue

Neil Martinson, Photographer

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

Neil Martinson documented the working life of Hackney and the East End throughout the seventies and eighties. Neil was born and brought up in Hackney, where he started taking street scenes and became a founder member of the Hackney Flashers photography collective.

Cheshire St

Steve Manning

Ridley Rd Market

Brian Simons

Bethnal Green Rd

Tony Kyriakides

Ken Jacobs

Ken Jacobs

Brian Simons

Stoke Newington

Ridley Rd Market

Lew Lessen

Abney Park Cemetery

Photographs copyright © Neil Martinson

You may also like to take a look at

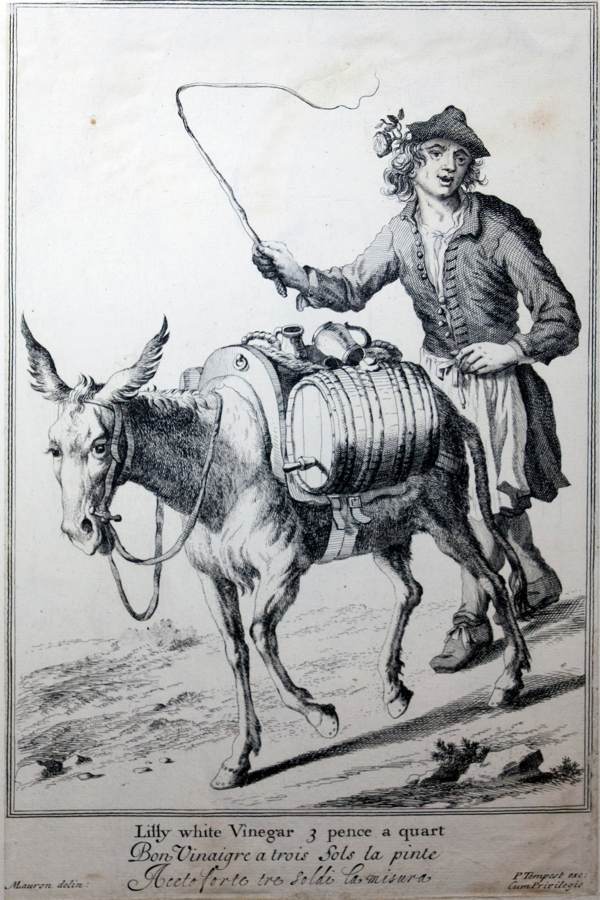

Marcellus Laroon’s Cries Of London

CLICK HERE TO BOOK YOUR TICKET

Today it is my pleasure to publish Marcellus Laroon’s vibrant series of engravings of the Cries of London reproduced from an original edition of 1687 in the collection at the Bishopsgate Institute

The death of Oliver Cromwell and the restoration of Charles II made the thoroughfares of London festive places once again, renewing the street life of the metropolis. After the Great Fire of 1666 destroyed the shops and wiped out most of the markets, an unprecedented horde of hawkers flocked to the City from across the country to supply the needs of Londoners .

Samuel Pepys and Daniel Defoe both owned copies of Marcellus Laroon’s Cries of London. Among the very first Cries to be credited to an individual artist, Laroon’s “Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life” were on a larger scale than had been attempted before, which allowed for more sophisticated use of composition and greater detail in costume. For the first time, hawkers were portrayed as individuals not merely representative stereotypes, each with a distinctive personality revealed through their movement, their attitudes, their postures, their gestures, their clothing and the special things they sold. Marcellus Laroon’s Cries possessed more life than any that had gone before, reflecting the dynamic renaissance of the City at the end of the seventeenth century.

Previous Cries had been published with figures arranged in a grid upon a single page, but Laroon gave each subject their own page, thereby elevating the status of the prints as worthy of seperate frames. And such was their success among the bibliophiles of London, that Laroon’s original set of forty designs – reproduced here – commissioned by the entrepreneurial bookseller Pierce Tempest in 1687 was quickly expanded to seventy-four and continued to be reprinted from the same plates until 1821. Living in Covent Garden from 1675, Laroon sketched his likenesses from life, drawing those he had come to know through his twelve years of residence there, and Pepys annotated eighteen of his copies of the prints with the names of those personalities of seventeenth century London street life that he recognised.

Laroon was a Dutchman employed as a costume painter in the London portrait studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller – “an exact Drafts-man, but he was chiefly famous for Drapery, wherein he exceeded most of his contemporaries,” according to Bainbrigge Buckeridge, England’s first art historian. Yet Laroon’s Cries of London, demonstrate a lively variety of pose and vigorous spontaneity of composition that is in sharp contrast to the highly formalised portraits upon which he was employed.

There is an appealing egalitarianism to Laroon’s work in which each individual is permitted their own space and dignity. With an unsentimental balance of stylisation and realism, all the figures are presented with grace and poise, even if they are wretched. Laroon’s designs were ink drawings produced under commission to the bookseller and consequently he achieved little personal reward or success from the exploitation of his creations, earning his living by painting the drapery for those more famous than he and then dying of consumption in Richmond at the age of forty-nine. But through widening the range of subjects of the Cries to include all social classes and well as preachers, beggars and performers, Marcellus Laroon left us us an exuberant and sympathetic vision of the range and multiplicity of human life that comprised the populace of London in his day.

Images photographed by Alex Pink & reproduced courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

Peruse these other sets of the Cries of London I have collected

More John Player’s Cries of London

More Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders